THE ARCHITECT´S MIND

“We are not here to create the most beautiful buildings in the world, but to build the world’s most beautiful way of life.”

— Bjarke Ingels

CREATIVITY MEETS FUNCTIONALITY

Introduction

The mind of an architect is a space where intuition dances with logic, and where aesthetic vision coexists with structural precision. Architecture is not solely about building; it is about shaping human experience through the creative orchestration of form, space, and purpose. The tension—and synergy—between creativity and functionality lies at the core of architectural practice.

This essay explores how architects navigate the balance between imagination and practicality, drawing on the provocative and playful design philosophy of Bjarke Ingels in Yes is More and the psychological analysis of the design process by Bryan Lawson in Creativity in Architectural Design. Together, these works reveal that the architect’s mind is not divided between art and science, but rather operates as a unique fusion of both—an alchemy where ideas become space.

Creativity as a Process, Not a Gift

In Creativity in Architectural Design, Bryan Lawson dismantles the myth of the “genius architect” by analyzing creativity not as an innate gift but as a practiced process. His research suggests that creative design emerges from iterative exploration, problem-framing, and the constant reframing of constraints. Architects, Lawson argues, are not merely solving problems—they are also discovering them.

Creativity in architecture, then, is not linear. It evolves through sketches, models, discussions, failures, and breakthroughs. This dynamic mirrors the psychological process of “divergent thinking,” where many potential ideas are generated, and “convergent thinking,” where those ideas are refined into workable solutions. Architects continuously oscillate between these modes.

In this light, functionality is not the enemy of creativity—it is its fuel. Constraints such as budget, climate, regulation, or material availability do not stifle innovation; they catalyze it. As Lawson demonstrates, the most compelling designs often arise when architects embrace limitations as part of their conceptual toolkit.

Bjarke Ingels: “Yes is More” and Pragmatic Utopianism

Bjarke Ingels, one of the most influential architects of the 21st century, embodies the idea that creativity and functionality are not opposing forces but partners in design. In Yes is More, a graphic-novel-style manifesto, Ingels lays out his “pragmatic utopianism”—a design philosophy that seeks to improve quality of life while responding intelligently to real-world conditions.

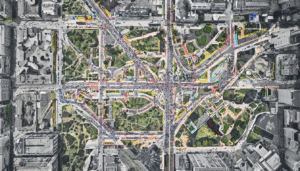

Projects like the VM Houses in Copenhagen or the Amager Bakke power plant illustrate how Ingels and his firm, BIG, turn complex functional challenges into opportunities for innovation. The power plant, for instance, is not just a waste-to-energy facility—it is also a ski slope. This hybrid program reflects a deep understanding of urban needs, ecological constraints, and playful creativity.

Ingels’ approach reframes the architect’s role from “problem-solver” to “opportunity-maker.” Rather than seeing function as a checklist to satisfy, he integrates it into the DNA of form-making. His buildings are bold and unconventional, yet rigorously logical—every curve, twist, and terrace serves a purpose, from airflow to social interaction.

The Dialogue Between Imagination and Real-World Demands

While creativity brings vision to architecture, functionality anchors it. The best architectural works result not from choosing one over the other, but from allowing both to engage in constant dialogue. Lawson emphasizes the importance of feedback in the design process—between the designer and their drawings, between the team and the client, between the idea and the physical reality.

This feedback loop mirrors the “design thinking” approach, where prototyping and iteration are essential. Each model or sketch becomes a question rather than an answer, prompting new insights. Architects must test their ideas not only against technical standards but also against social, environmental, and emotional criteria.

Bjarke Ingels’ projects illustrate this iterative dance. His designs are bold, but not reckless; experimental, but not impractical. He often engages with local communities, city planners, and engineers early in the process. By weaving functionality into his creative explorations from the outset, he avoids the trap of “form for form’s sake.”

Creativity with Consequence: Ethical Dimensions of Design

Another crucial aspect of the architect’s mind is ethical responsibility. Creativity without consideration can lead to alienating or unsustainable architecture. Functionality without creativity can result in sterile environments. Lawson and Ingels both advocate for a holistic design mentality—one that considers long-term impact.

In today’s world, architectural creativity must address urgent issues: climate change, urban density, inclusivity, and mental health. Ingels’ designs often incorporate renewable energy, green spaces, and communal areas. He shows that creative form can serve public good without compromise.

Lawson’s work reminds us that architects are not isolated artists; they are embedded in a web of social responsibilities. Their designs affect how people live, move, work, and feel. The creative process must therefore be empathetic, inclusive, and aware of its consequences.

Conclusion: The Architect’s Mind as a Living Studio

The mind of the architect is not a place of division, but of synthesis. It is where creativity and functionality intersect in complex, iterative, and meaningful ways. From Bryan Lawson’s psychological insights to Bjarke Ingels’ bold experiments, we see that the design process is not just about solving technical problems—it’s about imagining better ways to live.

Architecture, at its best, is not just an answer to a question. It is an invitation to experience life more deeply, more joyfully, and more consciously. And this begins in the mind of the architect—where ideas are born, tested, and ultimately built into the world.