ARCHITECTURE THROUGH TIME

"Architecture is the will of an epoch translated into space."

— Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

EVOLUTION OF BUILDING STYLES

Introduction

Architecture is one of the most expressive and enduring forms of cultural identity. Through its walls, columns, and roofs, we can read the story of civilizations, their beliefs, values, and technological capabilities. But architecture is not static—it evolves. Styles shift, sometimes gradually, sometimes in radical leaps. These changes are not only aesthetic; they reflect shifts in thought, religion, politics, economics, and the human understanding of space.

This essay explores the evolution of architectural styles across time, drawing from Spiro Kostof’s A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals and David Watkin’s Style, Structure, and Architecture. It traces the movement from sacred, ritualistic spaces of antiquity to the expressive modern forms of the 20th century and beyond. Rather than presenting style as mere ornament, both Kostof and Watkin encourage us to see style as an intellectual and cultural expression—deeply tied to how societies see themselves and their place in the world.

Architecture as Cultural Expression: Insights from Kostof

Spiro Kostof’s work presents architecture as inseparable from its historical, social, and ritual context. He rejects the idea of architecture as an isolated object and instead invites us to see it as a setting for life, deeply woven into the fabric of culture. For example, in ancient Mesopotamia or Egypt, architecture was a tool of divine communication. The ziggurat or pyramid was not only a building—it was a symbol, a ritual axis connecting humans to gods.

Kostof emphasizes that style in ancient architecture was rarely about personal expression. It was codified, symbolic, and communal. The Greek orders, for instance, were not arbitrary design choices—they reflected proportion, harmony, and the values of civic order. Similarly, Roman architecture, with its triumphal arches and grand forums, symbolized empire, power, and unity.

The transition from classical to medieval styles reflects more than a change in forms; it marks a shift in worldview. The Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals, rising with pointed arches and ribbed vaults, reflected a cosmos centered on faith, not reason. Light became divine. Verticality became aspiration. Style, in this sense, was theology expressed through stone.

Watkin’s Critique: Structure is Not Enough

In his article Style, Structure, and Architecture, David Watkin argues against a common modernist reduction: the belief that structure alone defines architecture. For much of the 20th century, architects dismissed style as superficial—a distraction from “truthful” structure or function. Watkin challenges this, asserting that style is inherent to architecture’s identity, not an afterthought.

He defends ornament and historical reference as intellectual choices, not nostalgic decoration. For Watkin, a building’s structure is its skeleton, but style is its character, its soul. He draws attention to how stylistic decisions reflect broader philosophical ideas—Renaissance balance and humanism, Baroque drama and power, Neoclassical order and rationalism.

The implication is that we cannot understand architecture without considering style as a mode of thought. Each historical period expressed its ideals through its buildings—whether the perfection of Platonic forms in the Renaissance, or the industrial sublime of the 19th century’s iron and glass constructions.

Modernism and Its Discontents

The 20th century marked one of the most radical ruptures in architectural history. The modern movement, led by figures like Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, sought to erase historical styles and begin anew. Their motto, “form follows function,” became a mantra of rational design—clean lines, open plans, and rejection of ornament.

While modernism achieved great innovation, it also provoked critique. Watkin argues that this anti-style ideology was itself a style, one with philosophical roots in Enlightenment rationalism and industrial logic. Modernism’s apparent neutrality masked a deep ideological stance.

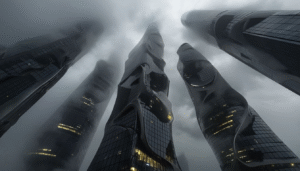

Kostof, too, is wary of architecture that forgets its human and historical context. He reminds us that buildings must respond to the rituals and rhythms of human life. When style is removed in favor of abstract purity, architecture can become alienating. The uniform towers of post-war urbanism, for example, often failed to create meaningful public spaces.

The Return of History: Postmodernism and Beyond

By the late 20th century, architecture witnessed a re-engagement with history, symbolism, and narrative. Postmodern architects like Robert Venturi and Michael Graves revived classical references, not out of nostalgia, but as a way to re-humanize architecture. They rejected the “machine aesthetic” of modernism and celebrated ambiguity, complexity, and irony.

David Watkin welcomes this return to stylistic pluralism. He sees it as an acknowledgment that architecture is not only about solving problems—it is about communicating meaning. A building, like a text, can tell a story, reference a tradition, or evoke emotion. This does not mean returning to old forms blindly, but engaging them critically and creatively.

Contemporary architecture continues to evolve with new materials, technologies, and environmental concerns. Yet even today, as parametric design and algorithmic processes shape cutting-edge buildings, the question of style remains relevant. How a building looks still matters—because it speaks to how we see ourselves.

Conclusion: Style as the Language of Time

The evolution of architectural styles is not a linear sequence of trends; it is a dialogue across time between form, function, and meaning. From the sacred geometries of antiquity to the digital fluidity of the present, architecture has always expressed the aspirations, fears, and values of its age.

Spiro Kostof teaches us to see buildings as settings for life—rooted in ritual, culture, and the human condition. David Watkin reminds us that style is not trivial but essential; it is the lens through which architecture becomes legible, emotional, and alive.

In this journey through time, we are reminded that architecture is more than shelter—it is identity in built form. And as we move forward, the challenge will be not to abandon style, but to use it wisely—to build not only with structure, but with meaning.